“The myriad of things one can do with one's time; so to consider performance is a radical act in and of itself when you’re a mother.”

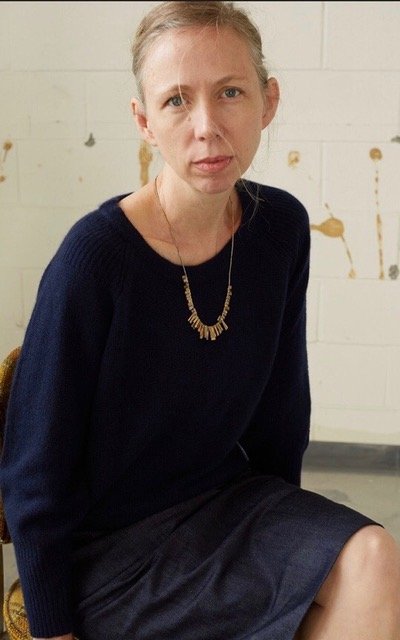

Justine Lynch Interview

Interviewed on September 28th, 2022

by Anabella Lenzu

Anabella: Thank you for being here and sharing your life and your art. The first question that I have for you is how did you become a mom? How are you dealing with all this, being a mother and being an artist?

Justine: I don't see them as separate. I have been taught that the uterus is a creative force for a woman. How I think the question lands is around resources. How much blood and time could go past the choice, which is to take the child to the next level. If there’s a choice to make a child, or for me it was children, the creative response to all the responses around the creation of a human and all that it entails to let go of the result while taking the action, the fruitful action is to me not separate from being an artist.

At the same time, it was the last performance that I made, they were in my uterus in the first trimester. I haven't made work that has been seen by an audience since. Which is 11 years, but I have not stopped being an artist or a dancer. They don't leave me. There’s been an imperative… I didn’t know if I would ever consider making something for audiences again. I didn't know if I had a need or if there was a need. If there was a place in my muse in relation to me as a creative being, to make something for the witness of an audience.

Two years ago, I was asked a question about myself as an artist and was given the opportunity to have 9 days to return to that relationship. I realized even though I haven't left and I don't know where it’s going, there is something actually important about creating performance from the lens of the mother. For me, it’s important to use the word mother. I know that we may have to use a different word in the greater scope but for me, it had to do with the relationship to the earth, the children that are coming into this world, and their children.

Anabella: It’s not a coincidence that your last performance was when you were pregnant during the first trimester. It coincides with perhaps a completely different journey for yourself as an artist and as a person. We met through the Parents Artist in Residency at Movement Research In 2022, did this residency unlock something different in you now that your kids are 11 years old?

Justine: I think that the residency brought me back into a relationship with the studio. I’ve been dancing in nature mostly or in spaces that were unconventional. Not in the studio, which is something I have a huge relationship with as a classically trained dancer. It's a very formal setting and it’s actually a little harder to feel my relationship to the earth and the mother in a dance studio. The studio is very masculine, very square, and clean. But my question was could I connect to something primal in me that didn’t have meaning imposed on top, as far as moving… as somebody who grew up in the modern dance world a lot of the work I was in had a combination of an aesthetic angle and a very meaningful particular view. I was just asking myself to really open that up and see what came through even basic things –– like the love of dancing and moving my body. I work in relationship to my teacher who is a direct voice towards this exploration. I think what really came from the residency was the rigor…my strength of being a mother. There's a certain central axis that can get pulled out. Just connecting to my central axis in a different way and focusing in that way, was part of the work for me –– also asking a simple question. This time was given to me and I honored it, but why would I take time away from parenting and making money or in prayer? The myriad of things one can do, with one's time! To consider performance is a radical act in and of itself when you’re a mother. What actually matters to me? So those are questions I thought of. I think something of the time, was making a different relationship with these questions. To actually work with the dance artist in me is not just –– maybe this is grandiose –– but it’s not just for me. It’s for my daughter's daughter. I grew up with a mother artist who prioritized her relationship to her muse above all else. She was certain there. For me, it was important to actually feel the necessity of the questions in me. The necessity of not prioritizing it above all else, but the necessity to even do it.

Anabella: I understand. Your mom was a dancer?

Justine: A painter.

Anabella: Let’s talk a bit about this. Some of the women I’ve interviewed only have boys. Ourselves were actually inside of our grandmother. Thinking about this feminine lineage of your mother, yourself, and your daughters. Can you talk about how it is to be female in this world? It’s interesting because of gender roles now. Men cannot be mothers, but they can be fathers.

I’d love to hear you speak about this lineage a bit.

Justine: As I create and work with performance, a poem came through for me, which is a central axis that I’m working with –– which is “Hello, Daughter.” It’s a poem that came through as I was working which has to do with the repair needed, especially in the genealogy of a white American woman. My concern isn’t just for my daughters, it’s for the daughters who are coming and our relationship to the great feminine…to the earth really. To me, it seems like the work right now that matters have to do with being aware of what has been cut, what has been taken from my ancestors, and the separation that has been created in the world, through racism, capitalism, misogyny, all of the ways in which things have separated. And also the lineage of artists along the matrilineal line, at least in my family was very wild, very powerful. Not always ethical. In this generation, I am interested in ethics alongside the wild feminine. I wonder if something could change in this world without the gaze of the mother, or without artists who are mothers.

Anabella: I think many things can change and that’s why I’m doing this project. What do you think your responsibility is in all of this, thinking about making performance –– specifically thinking about it for the next generation?

Justine: I think owning the responsibility is the question. If we don’t take any responsibility –– I don’t want to be too esoteric –– but I think it’s the responsibility to hold light. I have been taught that. I think an artist is able to work with light, which is what the world needs. So it may be a very small little candle, but it’s still what must happen. I don’t know how yet, because I have a real feeling of urgency and responsibility. I don’t yet have a container for where exactly I think it will go, but I do think without considering the questions at the root of what is separating mothers from being and acknowledging themselves as artists or a creative force, we lose the thread of how life matters. It’s actually in the generation and the creation of life that we find something that matters. Like hope, for example, we have to live only on this day, but hope has to travel. It’s the same as life. Life is a creative force, and by choosing to care for the next generation of life we give up ourselves. We have this strange idea in our culture that it’s wrong –– that service is wrong. That somehow if we give up ourselves, we are losing. Actually, it’s only through doing that, that we are taking responsibility.

Anabella: It’s huge. I was giving that example because for me as an immigrant, I’ve been here for 16-17 years and some things in this culture I still don’t understand. Being a mother and bringing your kid to public schools and thinking about the mass shootings, I don’t understand it and the majority of the people committing these crimes are men - not women, not mothers for sure - but they all have mothers. So it makes me think of these responsibilities, these social responsibilities.

For me, I’m Argentinian, but I have two American kids. What does this mean for me and my transfer of responsibilities? As I’m creating I’m thinking about my daughter's generation.

Going back for a second to what you said about calling the studio a “masculine space,” I feel this coldness and sterility…that’s not a creative home. How do you transform your art changing from the dance studio and the dance space, I understand your radical thinking and I’m very much in the line of your work. How do you explain this for someone who can’t imagine it or who is not a mother and doesn’t understand it?

Justine: I took it as a challenge to be in the studio. Where is the light falling? There was one improvisation that I videotaped that was of me working with the light coming through the window of the studio, as there was a warmth there and it was something I could make a relationship with. It’s useful, just like when you’re in an apartment, we don’t live in huts, we have homes and toilets and those kinds of things. For me it’s an awareness, for not being in the studio for so long, it brought a new awareness for me. I love that masculine space, we’re not talking about not loving the masculine, it’s part of the life too. It’s just making that adjustment, after I’ve been dancing with my feet a little closer to the earth. It feels a little less of a formal relationship to movement, meanwhile in the dance studio…it’s a wonderful container and it pairs everything away. I was very grateful for it.

It’s interesting when you spoke about the generations to come because one thing I’d like to be clear about is I don’t really care about making work that lasts a long time, the work itself. I actually believe that things should have a death, so there’s a light that’s carried through that and that’s what matters to me. Really when I think about some of the work that matters to me, it’s not so much about the steps, but it’s when there’s a light in it and I can feel it. It moved my heart and it made me feel that the body can be experienced through me, I can feel something, in a new way as an audience member in a different way. I can viscerally remember the amount of performances that have done that to me in my lifetime –– there aren’t that many.

For me, I consider myself one among many. I don’t consider myself a great choreographer, but I am very interested in light and in things that are real. It’s a contribution of a perspective.

Anabella: What do you think makes a “good mother” and what makes a “good artist”?

Justine: I think that our culture has a problem with motherhood and it’s very quick to kill the mother. All mothers are human and a good mother is a mother who can love through action and through her heart. I think I’ve been battling that perfectionism my whole life, not just as a mother, but as a daughter. I hesitate there, it’s a loaded question. To struggle with who we are, to say a “good” versus a “bad” mother. Who are we to say the bad mother we got didn’t create every problem we needed to become an artist? Because everything has to break in us. There is something about recognizing the creativity in myself that makes me a better mom. I don’t think being a good mom is having rules. I think being a good mom is being able to respond and that response is different all the time. You can respond to something that isn’t a want or a need, you are my children. There’s a difference between addiction and response.

Anabella: And once you think that you’ve finally got the hang of it, you don’t because your children continue to grow and change and expand.

Justine: Constant change: that’s what life is. Being an artist has to do with a combination of rigor, feeling, and following something. I don’t know at this point if I could be a good artist without following the light of those who have come before me. Following something in the dark that I can’t see and knowing others who have maybe walked a few steps ahead of me, is not a traditional definition. You may call that an apprenticeship. I think to really be able to respond as an artist and to make relationships with my muse takes a lot of willingness and humility. To attempt to make something real. The question I think of is creating something coming from my ego or from something deeper and that is a trick and I need support there. I have a good relationship with the ego, the artist. I’ve spent a good amount of time there and that’s not really interesting to me as a mother.

Anabella: When you say that. it makes me think it’s actually quite similar –– to be a mother and to be an artist. We’re not apprentices of our own kids, you know?

As you mentioned the continued transformation, the questioning, the ego, you mentioned you can’t be a mother if you’re selfish, but it’s the same thing, you can’t be an artist if it’s all about me.

Justine: The service.

Anabella: This idea of service that is inherent in both, being an artist and a mother, together.

Justine: And I think in service to what? As there’s no way I could actually step into the artist without service to my higher self and service to what I would call God, but what others might call something else. So it is service, but the problem is that the mother is supposed to be the martyr and that’s not service. The mother is the martyr in our culture, you’re supposed to give everything. It’s what our culture says –– to give everything to your children and then you’re a good mother. I’ve fallen into that trap, but I think there’s no way to have intimacy with myself as a creative person or intimacy as a mother if I’ve given everything away. It’s balance, there’s no right way to be a mother. There’s no rule book saying if we’re just in service to our children then we’re good mothers because there are so many pitfalls around there. What in our children are we in service to? Their wants and needs? Or about them being able to see the light in our eyes? Where is that service really landing? Especially in a culture where the mother is so easily killed. She’s supposed to give everything and not take anything, but if that’s really true then she has nothing left to give. The relationship to the artist in me is really a way to cultivate the light and hopefully, that light will shine for my children.

Anabella: I agree 100%

Justine: You can go in either direction, too far.

Anabella: Absolutely, but it’s a continued balance to listen to your needs and the needs of your family. It’s always in fluctuation –– to be in tune, being in the moment, and being present and available to listen to your needs.

Many of the choreographers I’ve interviewed say that the studio is my sacred space because the only time I’m able to be alone is the bathroom and the other place is the studio. That’s a very drastic statement, to say you’re depriving yourself essentially and thinking about how that translates to your children’s happiness. If you’re not happy for yourself and taking time for yourself or are frustrated; so everything needs balance and needs a middle point.

Justine: It’s a very strange world. Art was taken out of the earth and brought into the studio; now it is like the Western idea of meditation –– you sit in a quiet, perfect room and everyone is perfect. Meanwhile, as a mother you need to find the sacred in making rice or wiping the spit off of your child’s mouth. It’s a sacred act to be in the fluids and the juice of life if you bring love there. We don’t do it consciously all of the time…it happens for me when I get hungry, angry, lonely, or tired that I can’t connect…children are very loud. I’m a bit of a mystic, I like a quiet place myself, but to meet that force…the creative force in them. I’m over 50, but there’s a lot of energy in a small person, so I can’t live my life where my sacred space is only over there…it’s got to be here too. Always.

Anabella: Always. It’s so wonderful to meet you! It’s a wonderful part of this project, to meet each other. To inspire and encourage each other and have wonderful conversations.

Many times I feel we’re in the busiest time of life –– doing everything for you and your child, but this support system, this network makes you realize you’re not alone. And talking to everyone gives us different perspectives.

Justine: Well, thank you for asking me. I’m really grateful for the talk and am happy to keep the conversation open.

JUSTINE LYNCH L.Ac.,M.Ac. has been dancing for 51 years. In 1977-78 she performed with Batya Zamir. She received entrance in late auditions to LaGuardia H.S. graduating in 1988. And received her BFA in Dance from SUNY Purchase 1992. She performed as a founding member of Dance by Neil Greenberg from 1991-2006, with roles made for her by the choreographer in the seminal work Not About AIDS Dance. Her career as a dancer also included performing with Sarah Rudner and Roseanne Spradlin among others. She received her Masters in Acupuncture from MUIH in 2003 and began to weave her experiences with the elements of life into her work as a dancer and choreographer. Her own work has been performed at P.S. 122 in 1998, The Kitchen in 2009 and Judson Church with Movement Research in 2008 and 2011. As an artist, Justine’s work has sought to explore how movement is communication between worlds. She is influenced by the Master Teacher Laura Stelmok and is currently reshaping her conversation as an artist under Stelmok's training.

ANABELLLA LENZU: Originally from Argentina, Anabella Lenzu is a dancer, choreographer, scholar & educator with over 30 years of experience working in Argentina, Chile, Italy, and the USA. Lenzu directs her own company, Anabella Lenzu/DanceDrama (ALDD), which since 2006 has presented 400 performances, created 15 choreographic works, and performed at 100 venues, presenting thought-provoking and historically conscious dance-theater in NYC. As a choreographer, she has been commissioned all over the world for opera, TV programs, theatre productions, and by many dance companies. She has produced and directed several award-winning short dance films and screened her work in over 200 festivals both nationally and internationally.